An Innovative Approach to Corrective Feedback through the Use of Video for Sticky Teaching

Intermediate Grammar ENFL 037-02 (11 students) and Advanced Elective Grammar ENFL 171-02 (16 students) were the two courses that were the focus of this project. The main goals of the project were twofold:

- To create short grammar video explanations to be used as corrective feedback for students and to time how long the creation process took for each video

- To find out to what extent students found these video explanations that were provided in the form of individualized, corrective feedback to be helpful.

In previous grammar courses, each student in my intermediate grammar class has completed writing assignments in a Google doc that was shared between the student and me. I have provided written corrective feedback within the doc. This semester, however, in addition to providing written corrective feedback, for certain high frequency errors, hot links were pasted into my comments so that students could view a video explanation targeted at their specific errors. This is different from grammar video explanations that I have shared with students in the past in one critical way. In the flipped components of my grammar class in the past, video content was shared with all students before they really engaged with the material. Through this project, however, the links to these corrective feedback videos are shared with students with an individualized comment to a specific error that the student has made. The video explanations were created by using Explain Everything (an iPad application). Once a video was complete, it was titled and archived in a Google doc that served as the list of video resources. All of the videos were uploaded to YouTube.

There were two simple questions that I wanted to know about student behavior. First of all, I wanted to find out whether students preferred to do their writings in a Google doc or in a more traditional way (with paper and pen/pencil). I also wanted to know if students actually watched the video explanations that I recommended via Google doc comments. On a larger scale, I aimed to discover if this innovative way of providing creative, individualized feedback would be embraced by my students. Before this project began, I had had an idea that this method of teaching could be wildly popular with my students and more importantly, successful. I think of this as "proactive" and "responsive" instruction because I am being proactive in anticipating the types of errors learners will make based on my teaching experience, and the instruction is responsive in that learners receive immediate instruction when it is necessary. It responds to their needs. In effect, I wanted to know if the students would be as excited about the prospect of this method of learning as I was.

To better contextualize my motivation for this project, I wanted to fundamentally change the way students receive feedback on some of their most common errors. An important SLA tradition is valuing errors as learning opportunities (Corder, 1967). Student errors are essential to learning, and without errors, this project would not be feasible. Another tradition, one grounded in language teaching seems to be teaching grammar in a linear fashion. In other words, content is taught to the entire class, regardless of what each individual student might already know. Additionally, the grammar that is taught conforms to the content in the syllabus or matches the course objectives. The reality, though, is that students make many common errors that might not be the focal point of a grammar objective for a particular assignment, and for that reason, we teachers might provide feedback. Or, if we do provide feedback, it might be a two-letter chicken-scratch etching on a paper. Does the student reflect on this error? These types of errors are often very predictable for a teacher who has taught grammar for many years and is familiar with the learner error types. That was where my challenge lay. I wanted to see if through video, I could get the students to notice what was previously unnoticeable to them.

It is important to note that I did not set out to create glorified whiteboard grammar explanations. I wanted to make the information "sticky". Any and everybody can create a grammar explanation by drawing on a whiteboard and filming it. I have students who make the same errors over and over. They are provided written and/or oral corrective feedback in response to the error. In my experience, this can often result in an "in-one-ear-and-out-the-other" effect. Furthermore, if I provide a written comment to a common problem, I have to write it over and over, potentially hundreds of times per semester. If I provide oral corrective feedback (for example, during office hours), then the explanation is provided in a single serving which cannot be retrieved at a later time. Also, a student might be more likely to acknowledge that (s)he understands when (s)he really does not because of listening skills or a lack of vocabulary. Furthermore, how often do we as instructors give "off the cuff" explanations or search for examples that might not be as effective as when we take the time to prepare a well-crafted form of corrective feedback. What makes these explanations different is that they adhere to "sticky principles of teaching". Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die (Heath, C. & Heath D., 2007) is a book that promotes the idea that in order to make an idea sticky, it should adhere to one of the five principles in SUCCES(S).

SUCCES(S)

- Simple – Keep the idea simple

- Unexpected – Surprise the learner

- Concrete – Use tangible examples

- Credible – Support your case with credible sources

- Emotion - Appeal to the learner's emotions

- Story – Tell a story to drive action through simulation

This sounds very simplistic, but this is how the videos that I created differ from other grammar videos that I have seen on the Internet. Another strength of the video explanation is the medium. Some of the video explanations that I created were based on in-class explanations that I have given, but the technology affords me the opportunity to better prepare the explanation and enrich it with visuals.

15 students across the two courses completed a standard ITEL Open Educational Resources (OER) Cohort survey that was sent via Survey Monkey. Survey questions focused on the use of technology at GU as well as the effectiveness of the use of technology in the course of focus for the project.

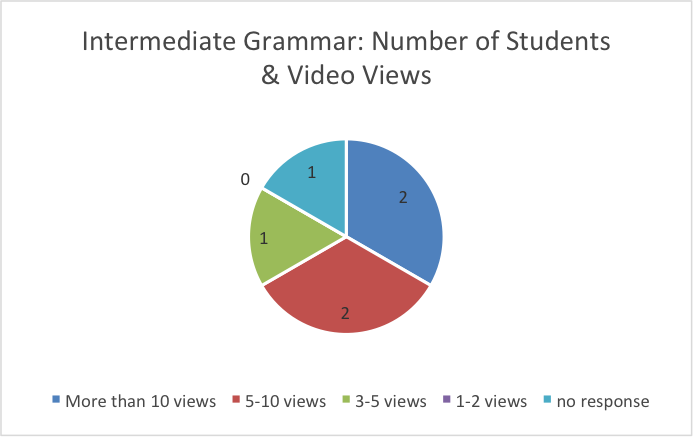

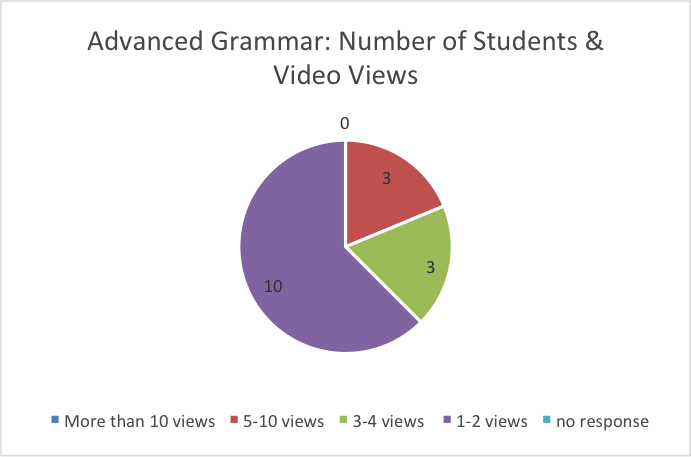

A Google forms survey was sent out to each student in both classes. Survey questions focused on student experiences related to viewing grammar videos that were accessed through their Google doc. 6 out of 11 students completed the survey in the Intermediate Grammar course. 16 out of 16 students completed the survey in the Advanced Elective Grammar course.

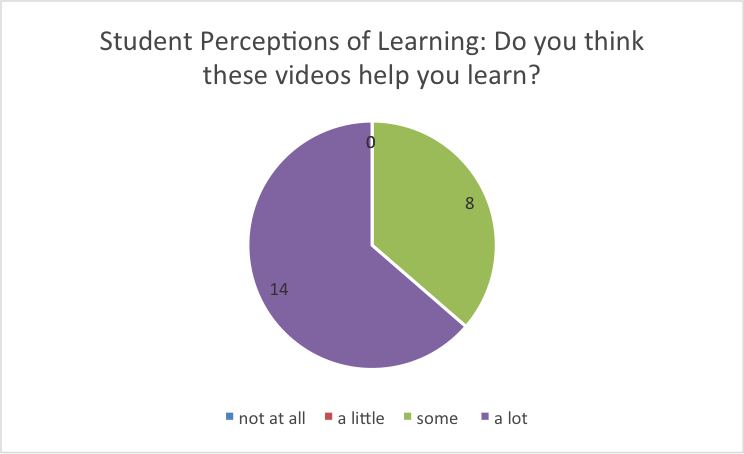

Survey data were compiled, organized, and tallied within a Google doc. Below are some of the findings.

Video Creation/Production

- Throughout the course of this project, 19 videos were created by the instructor. *Video creation is ongoing.

- The 19 videos took a total of approximately 13 hours and 40 minutes to create.

- The average video length is 1 minute and 24 seconds.

- On average, each video took 43 minutes to create.

Student Perceptions

- Most students surveyed (15 out of 22 respondents) prefer doing writing tasks in a Google doc versus completing writing tasks with paper and pen/pencil. Several students reported the use of a Google doc for writing purposes to be easier and more convenient than the paper and pen/pencil method.

- The video links appear to enhance learning from the students' perspective. 21 out of 22 respondents like receiving feedback on their errors through video links. Students who claimed to like this method of feedback reported the following about the videos (responses have been paraphrased).

- They are short, interesting, informative, sticky, to-the-point, easy-to-remember, focused-on-details, and clearer than written feedback.

- They allow for multiple views.

- They lead to fast comprehension.

- 4 out of 6 respondents in the intermediate class referred to the benefit of identifying mistakes and correcting them.

- One student out of 22 indicated a desire to have face-to-face feedback with the instructor.

- One student mentioned that a downside to the feedback was that (s)he could not ask an immediate question related to the feedback.

- Students prefer to learn by viewing grammar explanations versus reading grammar explanations. 19 out of 22 prefer to receive a video link over reading explanations in a book or online.

* It should be noted that the Intermediate Grammar class participated in this project for 16 weeks and 8 writing assignments. The Advanced Grammar class, in contrast, participated for 8 weeks and completed 4 writing assignments.

- There is a mixed reaction in comparing the video explanations to face-to-face explanations. Some students find the methods to be different, and others find them to be the same or similar.

- An advantage that multiple students point out in the video explanations is that they can be accessed anywhere at any time; multiple views are possible.

- One student acknowledges that classmates do not interrupt the video explanations.

- One student mentions that the video explanations include images and examples.

- Some students find the video explanations to be slower.

- Some students report not being able to ask immediate questions during the videos if they are confused.

- The fact that 100% of the respondents report that the videos help them learn more than “a little” is overwhelmingly positive.

Students were asked an optional question at the end of the survey, and 12 out of 22 students provided positive feedback about the learning experience. Ten students did not comment. Of the 12 anecdotal comments, the positive endorsements from student comments will motivate me to continue creating videos for grammar feedback.

The two primary goals of the project were:

- To create short grammar video explanations to be used as corrective feedback for students and to time how long the creation process took for each video

- To find out to what extent students found these video explanations that were provided in the form of individualized, corrective feedback to be helpful

With regard to the first question, I am now able to share with fellow faculty and other teachers who might be interested in taking on such a project the time investment that might be required. The time investment also appears to be justified. In terms of the second question, all of the students who participated in the survey report the videos to help them "more than a little". In this sense, both the instructor and the students view this method of learning to be beneficial. The anecdotal comments imply that that students like receiving this method of feedback, and they would like to receive more. Based on students' comments, some anecdotal evidence points to support claims that the content in the videos is "sticky", and therefore, it might lead to better retention of information. Given the fact that more than half of the students provided extra, positive comments regarding the videos suggests that students perceive their learning to be enhanced through this method of instruction.

This experience has been overwhelmingly positive for a number of reasons:

- The motivation for taking on this project was problem-driven. There are many common errors that many students make repeatedly. Therefore, I concluded that either I was not reaching my students through my teaching and/or feedback, or the feedback was not "sticky" enough for students to remember to apply in later language output. I felt that I could provide a better learning experience for students by changing the medium of feedback – through short video explanations. The grammar points that I targeted through this project are problem points for students in my context. I cannot claim that the problems have been solved, but there is evidence that points to the problems possibly being diminished.

- I was able to quantify the amount of work required for an instructor to create short videos. When I share my work with other faculty, they might be leery about taking on such a project because of the time investment. The time investment is already paying off. For example, on writing task 1 in my Intermediate Grammar class, during the first week of class this Spring 2015, I provided a student three different video explanations, and she had only written six sentences. Three needs for video feedback in a six-sentence document confirm that the "proactive" method of instruction is working. Typical errors are being anticipated, and videos to address the errors have been created. From an efficiency standpoint, the amount of time spent providing feedback for this student took approximately two minutes, and yet the student will receive approximately five minutes of video explanation (among the three videos).

- Not only has this project, along with the positive response that I have received from my students, inspired me to continue using these videos and creating new ones, but it has motivated me to eventually brand my own YouTube Channel and create a website that could be a larger scale Open Educational Resource (OER).

It must be acknowledged that this was a small-scale project conducted among 27 students across two classes. The instructor was also the creator and voice of the grammar explanations in the videos. It is unlikely that student perceptions of the effectiveness of the video feedback would be as positive if the students were in another class or in another institution. Though video explanations might be perceived as more impersonal than written comments to a student, the fact that videos have been created by the instructor and personally selected for a student in response to an error speaks to the value of the student-teacher relationship. Further research into student reactions to the videos in another class within the EFL program could be a good step to see if this project could be scalable.

To date, I have casually shared the nature of my project with a handful of faculty members within my department. However, on January 29, 2015, in an intradepartment professional development session, I will have an opportunity to more formally present and demonstrate how the product of this project can be shared and used throughout the EFL program. In addition, I have submitted a proposal to present at the Conference on Language, Learning, and Culture at Virginia International University, April 9-11, 2015. I also plan to submit a proposal to present at the TESOL Annual Convention, 2016 (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages) in Baltimore, MD.